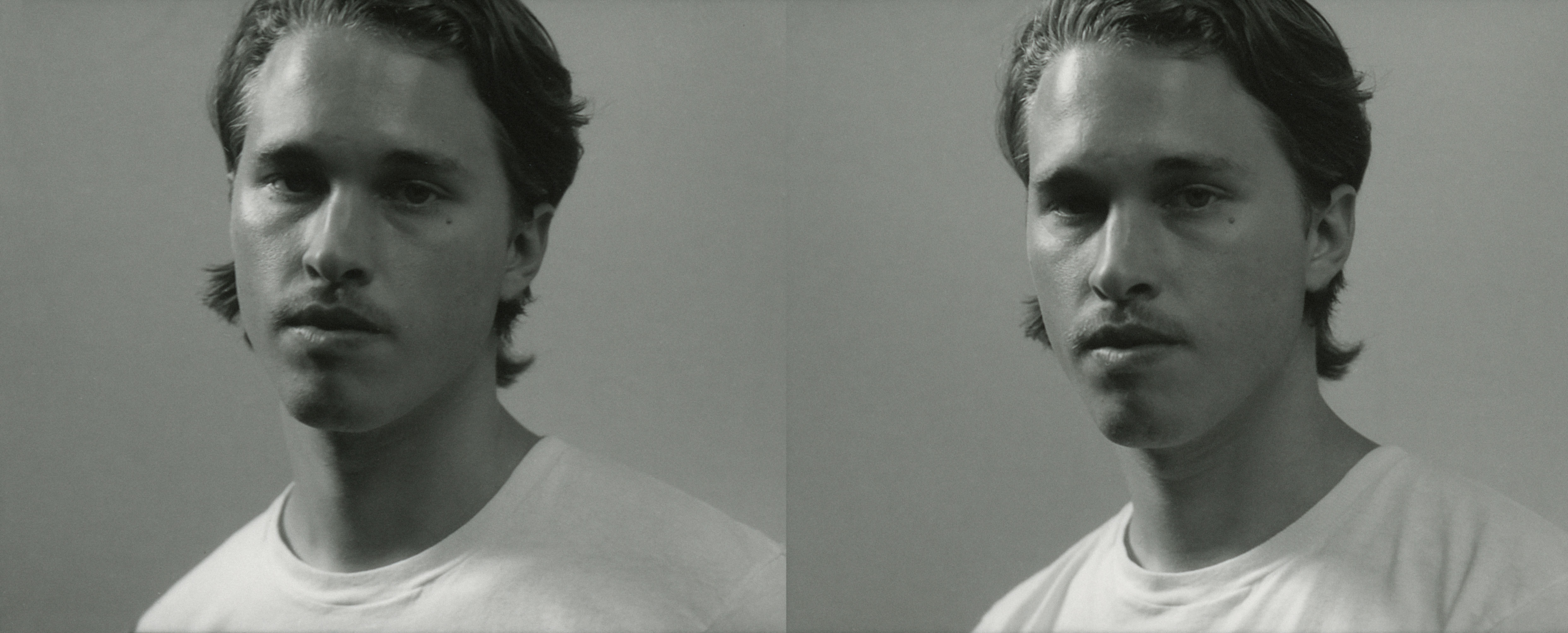

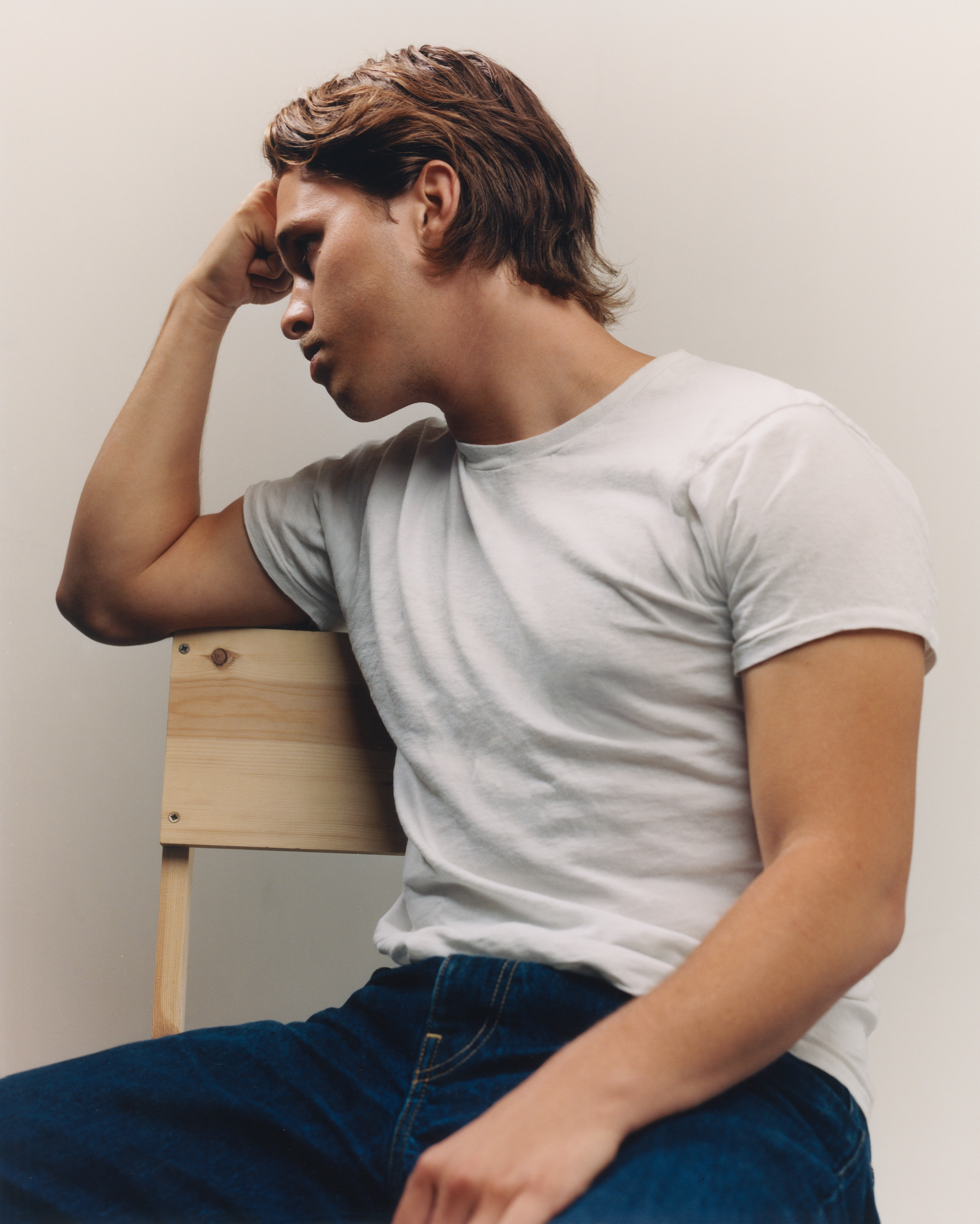

Ryan Beatty on the earth and emotional grit of his new album

Written by ABR on 12/07/2023

In March 2020, six weeks after the release of his sophomore album Dreaming of David, the musician Ryan Beatty went missing. The pandemic shut down America and Ryan – a man familiar with long periods of quiet, preferring them even – cancelled his tour, the only public commitment to his album cycle. That record – a paean of pent-up emotion that manifested in all shades of skewed vocal pitching and warped electronic production – bloomed in the hands of those who listened to it, but its maker had staged a disappearing act.

“That’s one way to put it,” Ryan says with a smile, over three years later in London. He only resurfaced recently. Having noticed the overdrive other artists went into back then, he opted for the opposite. “I found a lot of comfort in just being quiet. I wanted to live more life before I started making anything else. Sometimes people forget that that’s possible for themselves.” It is possible for Ryan Beatty, frugal with how he wears his fame; an intense thinker who favours solitude. If male artists his age – he turns 28 in September – have traditionally leaned into the material byproducts of music, Ryan’s work isn’t steered by opportunity. Each album falls unexpectedly like ripe fruit.

Ryan broke his three year silence in March this year by announcing a new album called Calico on Instagram. “i’ll save my monologue for another day,” the caption read, “but for now you should know that i’m smiling.” It was released two months later. Fans have since hailed it his masterpiece.

It is markedly different from anything he’s made before. His debut album, 2018’s Boy in Jeans, is an intelligent pop album about grabbing the reins of his adolescence after he was emancipated from a strange stint of childhood fame and, subsequently, came out as gay. At the same time, he was working closely with his friends Brockhampton, the since-disbanded rap group as a writer and vocalist. When Boy in Jeans was released, he got a DM on Instagram from Tyler, the Creator, who’d heard his track “Party’s Over”. The pair went on to collaborate on a series of Tyler’s projects, including 2019’s IGOR.

The follow-up Dreaming of David, a thematically opaque record with pangs of heartbreak, feels sullen and obscure sonically. Calico, in comparison, is crystalline: entirely acoustic, co-produced by Ethan Gruska and with instrumental contributions from Justin Vernon of Bon Iver. Its lyrics are replete with references to the vastness of the natural world. In one song “Bruises Off The Peach”, Ryan calls himself “careless like a comet”; the track “Hunter”, the record’s labyrinthine, seven-minute-long centrepiece, charts a walk into the wilderness, with lyrical mentions of mares frightened by thunder and lightning and the corpses of deers.

If it feels like a sharp left-turn to the traditional Ryan Beatty listener, that’s because it is; the artist has spent over a decade mulling it over. It’s inspired by artists and albums entrenched in a specific style of earthy Americana, like Hejira by Joni Mitchell and, he says, “the music my dad would play growing up”, like James Taylor and John Denver.

Work began on Calico in February 2021, when Ryan was introduced to Ethan by a mutual friend who thought they’d have something creatively in common. “I could tell he approaches music in an emotionally driven way,” he says of when they first worked together. “I approach it very similarly.” He was already familiar with his work: Ethan’s most prolific collaborator is Phoebe Bridgers, with whom he produced her albums Stranger in the Alps and Punisher. (Ryan calls Phoebe “incredible”.) He and Ethan wrote the song “Multiple Endings” together, a song that reads like a recollection of a break-up, the fogginess of a relationship when you’re in it, and how much is taken from you without you knowing.

For the rest of the year, Ryan wrote. “[Ethan and I] would start something then I’d leave and go live for a little bit longer and then work on the songs at home,” he says. He notes down lyrics, returns to them, scrutinises them. There was one day, at the hallowed Shangri-La studios in Malibu, where he spent 12 hours unpicking a single verse. “I can always sense it when it’s there but I don’t always have the words for it immediately,” Ryan says. “I can see the skeleton of the thing.”

“He holds himself to the highest standard,” Ethan tells me, “so much so that it can be pretty stressful and painful for him when he’s in the trenches on something. [But] all the pain and discomfort that rose up, like in any project, ended up being really worthwhile and essential.” By the time 2022 arrived, Ryan felt like he had finished. He had written deeper than he had wide – he insists there’s not much more music than the nine tracks present on the album. “Once I felt it in my gut,” he says, he knew: “That’s what it was.”

Ryan was raised in the city of Clovis in California, an original frontier town an hour’s drive from Yosemite National Park. Calico is, he says, “100%” a California record. “I felt things coming full circle at this point in my life,” he says. “I was thinking a lot about my childhood and things I grew up on, and allowing myself to remember that I’m a California boy through and through. I feel like it’s in my blood.” It feels like a record about home, I say. His mother is mentioned; his sister by name. He says he thought about Clovis “the whole time [he] was making it”.

“I left Clovis when I was 15 years old and that’s such a half-point,” he says. In a couple of years, he will have spent half of his life in Los Angeles. “I don’t know, in some weird way I had a lot of memories of my hometown. I guess it’s a place…” The sentence trails off. “I don’t wanna go on about it. That’s all I’ll say about that.” When he feels like has spoken for too long, about anything, he will find a way to stop.

The album was brought to life visually in collaboration with Peter de Potter, the Belgian artist known for his deconstructivist approach to imagery and his past collaborations with Raf Simons. He shot the album’s artwork and its music videos. “There are a lot of sub-stories and subjects across all of the imagery,” Peter tells me. “[Ryan] had the idea to work around certain activities that have a masculine/‘violent’ ring to them, like hatchets and arm wrestling, but to turn them around and make them poetic and speak of some inner battle.” In the video for “Cinnamon Bread”, Ryan engages in ceaseless arm wrestles. Instead of alluding to a heightened machismo, Peter felt the intention was “almost purifying”, adding: “It’s not about winning or losing – it’s more about going through the self-organised ordeal to reach a spiritual sense.”

This feels indicative of the plane Ryan makes art on; the way he considers things. I ask if he’s an emotional extremist. He laughs. “I‘d never put it that way,” he says, “but when I’m making music I’m at my most extreme emotionally because I allow myself to go there. Things mostly affect me when I’m by myself. I’m not one to burst out in tears somewhere. My emotions are intense, present in the music, but I still keep it to myself.”

This is one of the first times Ryan has discussed Calico publicly, despite it being nearly two months old. “The thing is I’m still unwilling to share a lot about [the album],” he says, “and not for any other reason other than I believe in keeping the mystery of things. It has to stay that way.” The process of unpicking his own lyrics doesn’t interest him.

The constant desire for artists to want to be known, and for their audience to know them fully, is an almost vulgar and uniquely modern invention. Ryan, however, would like to abscond that – and experiencing fame in general – as much as he can.

His lyrics tell you so: on “Cinnamon Bread”, he namechecks Infinite Jest, David Foster Wallace’s infamous novel about the toxic trappings of the entertainment industry. “It’s weird because I’ve never experienced it in an uncontrollable way,” he says of celebrity. (His industry roots gave him a taste of it, but that story has been told before.) “But when you submit yourself to the world… I don’t know if that sacrifice is worth it.” He’s conflicted: “I want people to know my music, and so I don’t want to sit here and say that I want to live under a rock because that’s just not true. But playing into it? I don’t know.”

Back when he had released Dreaming of David, Ryan had expressed a desire to be “less sacred” about his music and how he releases it. He smirks: “I’ve changed my mind about that.” At that point, he had no idea what was coming: years to toil at something under the cover of collective isolation. This time around, he gets to revel in it more: a tour kicks off in September; he has released visuals for his tracks with Peter. Slowly, crushingly emotional live recordings of the Calico tracks are making their way online.

Then there is whatever comes after this. An inevitable stretch of silence once again, followed by music that will appear, at some point, as if from nowhere. “I can tell what I’m leaning towards and that feels good,” he says of the Calico follow-up. “The last time I felt that was right before I made this record.”

“I see it in the distance,” he says, his forearms resting on the table in front of him. “I’m not reaching towards it. But it’s coming to me.”

Credits

Photography Daniel Adhami

Author

ABR

Reader's opinions

You may also like

Continue reading

ABR Group

ABR Group